The EU AI Act – Prepare for the coming EU Regulation –

We published a newsletter regarding The EU AI Act. To view PDF version, please click the following link.

→The EU AI Act – Prepare for the coming EU Regulation –

The EU AI Act

Prepare for the coming EU Regulation

April 2024

One Asia Lawyers Tokyo Office

Yusuke Tomofuji, Lawyer (State of New York, USA)

Goro Kokubu, Lawyer (Japan)

Bakuto Yamamoto, Lawyer (Japan)

1. Introduction

On December 9, 2023, the EU co-legislators, the European Parliament and the Council, reached a political agreement on the AI Act proposed by the European Commission in 2021.[1]

On March 13, 2024, the regulation was endorsed by MEPs with 523 votes in favor, 46 against, and 49 abstentions.[2] It is still subject to a final lawyer-linguist check and is expected to be finally adopted before the end of the legislature. It also needs to be formally endorsed by the Council.

The AI Act is considered as the first comprehensive law on AI and will have far-reaching implications for AI governance worldwide. The European Union is looking to set an example in this field and promote its model of AI regulation. That’s why this newsletter is dedicated to providing a detailed explanation of the upcoming regulation.

2. Overview

(1) Application and Scope

The AI Act will enter into force 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal, and will be fully applicable 24 months after it enters into force, except for bans on prohibited practice, (6 months after entry into force)[3]; codes of practice (9 months after entry into force); general-purpose AI rules including governance (12 months after entry into force); and obligations for high-risk systems (36 months).

The AI Act applies to providers[4] and deployers[5] of AI systems established in the EU or in a third country if the output produced by the AI system is used in the EU, and to affected persons that are located in the EU.

It does not apply to AI systems used exclusively for military, defense, and national security purposes, AI systems developed for the sole purpose of scientific research and development, and AI systems released under free and open-source licenses unless they are classified as high-risk AI systems under Article 6, prohibited under Article 5, or subject to transparency obligations under Article 52. Also, the AI Act does not apply to natural persons using AI systems in the course of purely personal non-professional activity.[6]

(2) The risk-based approach

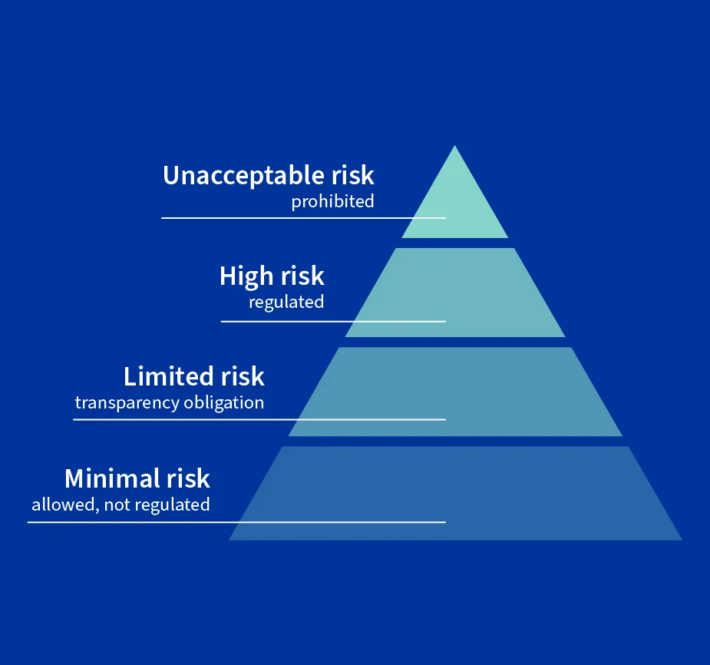

The AI Act follows a risk-based approach; the higher the risk of AI systems, the stricter the rules, as illustrated in the picture below.

(From European Council: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/your-online-life-and-the-eu/)

Specifically, the AI Act categorizes AI systems into four and regulates as below:

- Unacceptable Risk: Prohibited

- High Risk: Regulated

- Limited Risk: Transparency Obligations

- Minimal Risk: Allowed, not regulated

(3) A. Unacceptable Risk

Article 5 of the AI Act regulates prohibited AI practices. These are:

- Use of subliminal, manipulative, or deceptive techniques to materially distort a person’s or a group of persons’ behavior,

- Exploitation of vulnerabilities of a person or a group of persons due to their age, disability, social, or economic situation

- Biometric categorization of natural persons based on biometric data to deduce or infer their race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs, or sexual orientation[7],

- Social scoring,

- Real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement[8],

- Individual predictive policing (i.e., predicting the risk of a person to commit a criminal offense based on their personality traits),

- Untargeted scraping of the internet or CCTV for facial images to create or expand facial recognition databases,

- Emotion recognition in the workplace and education institutions, unless for medical or safety reasons (e.g., monitoring the tiredness levels of a pilot).

(4) B. High Risk

a. Category of High-Risk AI Systems

According to Article 6(2) and Annex III of the AI Act, AI systems used in the following areas are considered high-risk AI systems:

- Biometrics (remote biometric identification systems, biometric categorization, and emotion recognition),

- Management and operation of critical digital infrastructure, road traffic, and supply of water, gas, heating, and electricity,

- Educational and vocational training (admission, evaluation, and monitoring during tests),

- Employment, management of workers, and access to self-employment (recruitment, promotion, termination, evaluation, and distribution of assignments),

- Access to and enjoyment of essential private and public services (evaluating the eligibility for essential public assistance benefits and services; evaluating a person’s creditworthiness, or establishing their credit score; evaluating emergency calls; dispatching first response services; establishing emergency healthcare patient triage systems; conducting risk assessment and pricing of life and health insurances),

- Law enforcement (using polygraphs or similar tools; assessing the risk of a person of offending or becoming a victim of criminal offenses; evaluating the reliability of evidence in the course of investigation or prosecution of criminal offenses; assessing personality traits and past criminal behavior; conducting profiling in the course of detection, investigation, or prosecution of criminal offenses),

- Migration, asylum, and border control management (using polygraphs or similar tools; assessing a security risk, a risk of irregular migration, or a health risk posed by a person; examining applications for asylum, visa, and residence permits; detecting, recognizing, or identifying persons in the context of border control),

- Administration of justice and democratic processes (assisting a judicial authority in researching and interpreting facts and the law and applying the law to a concrete set of facts; influencing the outcome of an election or the voting behavior of natural persons).

While the above areas are defined as High Risk, AI systems are not considered high-risk if they do not pose a significant risk of harm to the health, safety, or fundamental rights of natural persons (Article 6(2a) of the AI Act). Specifically, this is the case if the AI system improves the result of a previously completed human activity, detects decision-making patterns not replacing or influencing the previously completed human assessment, and/or performs a preparatory task for any of the abovementioned high-risk cases.

b. Regulations on High-Risk AI Systems

AI systems that are deemed to be high-risk must be designed and developed with a risk management system in place.[9] They should also have technical documentation[10], allow automatic record-keeping through logs, and human oversight. Moreover, they should possess an appropriate level of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity. High-risk AI systems must be accompanied by instructions for use that provide concise, complete, correct, and clear information. These instructions should be easily accessible and comprehensible to users.

As outlined in Art. 14.4 of the AI Act, human oversight measures include the following:

(a) understanding the capabilities and limitations of the AI system and monitoring its operation accordingly;

(b) being aware of the risk of “automation bias”, which can occur when users rely too much on the output of the AI system;

(c) correctly interpreting the AI system’s output, using the available tools and methods as needed;

(d) making informed decisions about whether to use the AI system in any given situation, and/or disregarding, overriding, or reversing its output as necessary; and (e) intervening in the operation of the AI system, if needed, by using a “stop” button or similar procedure to halt the system safely.

c. Obligations of Providers and Deployers of High-Risk AI Systems

According to Art. 16 of the AI Act (unless stipulated otherwise), providers of high-risk AI systems must:

- Indicate their identity and contact details,

- Have a quality management system in place,

- Keep the technical documentation, the documentation concerning the quality management system at the disposal of national competent authorities,

- Appoint an authorized representative when established outside the EU,

- Ensure the AI system undergoes a conformity assessment before it is placed on the market or put into service in accordance with Article 43 of the AI Act[11],

- Make a written machine-readable declaration stating that the AI system conforms with the AI Act and with the GDPR if applicable (“EU declaration of conformity”)[12],

- Register themselves and their system in the EU database[13],

- Establish a post-market monitoring system that actively and systematically collects, documents, and analyzes relevant data[14]

- Report serious incidents to the national market surveillance authorities (Article 62).[15]

Deployers of high-risk AI systems have specific obligations under Article 29 of the AI Act. They must ensure that natural persons assigned to oversee the AI system have the necessary competence, training, authority, and support (Art 29.1a).Deployers must, in general, conduct a fundamental rights impact assessment (Article 29a of the AI Act).

(5) C. Limited Risk

Regardless of the aforementioned classification of risk prepared by the EU, there is no clear definition of what constitutes Limited Risk under the AI Act. However, AI systems that are intended to interact directly with natural persons are considered as Limited Risk AI Systems and such systems must be designed and developed in a way that ensures the concerned natural persons are aware that they are interacting with an AI system unless it is already apparent to a reasonably well-informed, observant, and cautious natural person considering the circumstances and context of use (Art. 52).

(6) D. Minimal Risk

Like Limited-Risk AI system, regardless of the aforementioned classification of risk prepared by the EU, there is no clear definition of what constitutes Mimimal Risk under the AI Act. However, as the use of AI systems in the course of purely personal non-professional activity (Article 2.5c) is excluded from the application of the AI Act, such is therefore considered to be Minimal Risk.

3. Enforcement

The AI Act imposes fines for violations as a percentage of the offending company’s global annual turnover in the previous financial year, or a predetermined amount, whichever is higher. This would be €35 million or 7% for violations of the banned AI practices, €15 million or 3% for violations of other obligations, and €7,5 million or 1% for the supply of incorrect information (Article 71 of the AI Act). The European Data Protection Supervisor may impose administrative fines on EU institutions, agencies, and bodies falling within the scope of the AI Act for non-compliance (Article 71 of the AI Act).

Any natural or legal person may submit a complaint to the relevant market surveillance authority concerning non-compliance with the AI Act. If a deployer makes a decision based on the output of a high-risk AI system that produces legal effects or significantly affects an individual’s health, safety, or fundamental rights, the individual has the right to request clear and meaningful explanations about the AI system’s role in the decision-making process and the key factors that contributed to the decision (Article 68c of the AI Act).

4. Measures Supporting Innovation

The AI Act promotes the development of AI, with so-called regulatory sandboxes established by national authorities to foster innovation and facilitate the development, training, testing, and validation of innovative AI systems for a limited time before their placement on the market or putting into service. Such regulatory sandboxes may include testing in real-world conditions supervised in the sandbox.

Testing of AI systems in real-world conditions outside AI regulatory sandboxes may be conducted by providers of high-risk AI systems subject to the approval of the national market surveillance authority and upon informed consent of the affected individuals (Article 54a of the AI Act).

5. Conclusion

The AI Act is centered around a risk-based approach. The AI Act differentiates risks and stakeholders related to AI system, and regulates them based on such differentiation. However, as stipulated above, personal or non-professional use is not covered by the regulation.

To conclude with the words of Dragos Tudorache (Civil Liberties Committee co-rapporteur of the European Parliament) this may indicate that the AI Act may be amended based on the development of AI systems: “AI will push us to rethink the social contract at the heart of our democracies, our education models, labor markets, and the way we conduct warfare. The AI Act is not the end of a journey but rather the starting point for a new model of governance built around technology.”

[1] The text can be found here: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5662-2024-INIT/en/pdf

[2] The text can be found here: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0138_EN.pdf

[3] Title I and II which includes Article 5 (Prohibition)

[4] “Provider” means a natural or legal person, public authority, agency, or other body that develops an AI system or has it developed and places it on the market or puts it into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge (Article 3(2) of the AI Act).

[5] “Deployer” means any natural or legal person, public authority, agency, or other body using an AI system under its authority except where the AI system is used for personal non-professional activity (Article 3(4) of the AI Act).

[6] Article 2 of the AI Act.

[7] Filtering of lawfully acquired biometric datasets in law enforcement will still be possible.

[8] It is allowed when strictly necessary for the following objectives: to search for a missing person, to prevent a specific and imminent terrorist threat, or to locate, identify, or prosecute a perpetrator or suspect of a serious criminal offense listed in Annex IIa to the AI Act. Those exceptions are subject to authorization by a judicial or other independent body and to appropriate limits in time, geographic reach, and the databases searched. The law enforcement authority must complete a fundamental rights impact assessment (Article 29a of the AI Act), register the system in the database according to Article 51 of the AI Act, and notify relevant national authorities.

[9] This means adopting targeted measures to eliminate the foreseeable risks to health, safety, or fundamental rights, or adopting mitigation and control measures, as well as informing, and training deployers (Article 9 of the AI Act).

[10] Annex IV of the AI Act outlines the information that needs to be included.

[11] The conformity assessment includes an assessment of the quality management system and of the technical documentation. The procedure is outlined in Annex VI and Annex VII of the AI Act.

[12] Annex V of the AI Act outlines the information that needs to be included.

[13] Except for high-risk AI systems in the areas of law enforcement, migration, asylum, and border control, the EU database will be publicly available and user-friendly (Article 60(3) of the AI Act).

[14] The post-market monitoring system shall be based on a post-market monitoring plan for which the European Commission will establish a template (Article 61(3) of the AI Act).

[15] “Serious incident” means any incident or malfunctioning of an AI system that directly or indirectly leads to the death of a person or serious damage to a person’s health; a serious and irreversible disruption of the management and operation of critical infrastructure; a breach of obligations under Union law intended to protect fundamental rights; or serious damage to property or the environment (Article 3(44) of the AI Act).